History

Main article: History of Bucharest

Bucharest’s history alternated periods of development and decline from the early settlements of the Antiquity and until its consolidation as capital of Romania late in the 19th century.

First mentioned as “the Citadel of București” in 1459, it became a residence of the Wallachian prince Vlad III the Impaler. The Old Princely Court (Curtea Veche) was built by Mircea Ciobanul, and during following rules, Bucharest was established as the summer residence of the court, competing with Târgoviște for the status of capital after an increase in the importance of southern Muntenia brought about by the demands of the suzerain power, the Ottoman Empire.

Burned down by the Ottomans and briefly discarded by princes at the start of the 17th century, Bucharest was restored and continued to grow in size and prosperity. Its centre was around the street “Ulița Mare”, which starting 1589 was known as Lipscani. Before the 18th century, it became the most important trade centre of Wallachia and became a permanent location for the Wallachian court after 1698 (starting with the reign of Constantin Brâncoveanu).

Bucharest in 1837

Partly destroyed by natural disasters and rebuilt several times during the following 200 years, hit by Caragea’s plague in 1813–1814, the city was wrested from Ottoman control and occupied at several intervals by the Habsburg Monarchy (1716, 1737, 1789) and Imperial Russia (three times between 1768 and 1806). It was placed under Russian administration between 1828 and the Crimean War, with an interlude during the Bucharest-centred 1848 Wallachian revolution, and an Austrian garrison took possession after the Russian departure (remaining in the city until March 1857). Additionally, on March 23, 1847, a fire consumed about 2,000 buildings of Bucharest, destroying a third of the city. The social divide between rich and poor was described at the time by Ferdinand Lassalle as making the city “a savage hodgepodge”.

Aerial view of the city in 1927

I.C. Brătianu Boulevard in the 1940s

In 1861, when Wallachia and Moldavia were united to form the Principality of Romania, Bucharest became the new nation’s capital; in 1881, it became the political centre of the newly-proclaimed Kingdom of Romania. During the second half of the 19th century, due to its new status, the city’s population increased dramatically, and a new period of urban development began. The extravagant architecture and cosmopolitan high culture of this period won Bucharest the nickname of “The Paris of the East” (or “Little Paris”, Micul Paris), with Calea Victoriei as its Champs-Élysées or Fifth Avenue.

Between December 6, 1916 and November 1918, it was occupied by German forces, the legitimate capital being moved to Iași. After World War I, Bucharest became the capital of Greater Romania. In January 1941 it was the place of Legionnaires’ rebellion and Bucharest pogrom. As the capital of an Axis country, Bucharest suffered heavy losses during World War II, due to Allied bombings, and, on August 23, 1944, saw the royal coup which brought Romania into the anti-German camp, suffering a short but destructive period of Luftwaffe bombings in reprisal.

During Nicolae Ceaușescu’s leadership (1965–1989), most of the historic part of the city was destroyed and replaced with Communist-style buildings, particularly high-rise apartment buildings. The best example of this is the development called Centrul Civic (the Civic Centre), including the Palace of the Parliament, where an entire historic quarter was razed to make way for Ceaușescu’s megalomaniac constructions. On March 4, 1977, an earthquake centered in Vrancea, about 135 km (83.89 mi) away, claimed 1,500 lives and destroyed many old buildings. Nevertheless, some historic neighbourhoods have survived to this day.

The Romanian Revolution of 1989 began with mass anti-Ceaușescu protests in Timișoara in December 1989 and continued in Bucharest, leading to the overthrow of the Communist regime. Dissatisfied with the post-revolutionary leadership of the National Salvation Front, student leagues and opposition groups organized large-scale protests continued in 1990 (the Golaniad), which were violently stopped by the miners of Valea Jiului (the Mineriad). Several other Mineriads followed, the results of which included a government change.

After the year 2000, due to the advent of significant economic growth in Romania, the city has modernized and is currently undergoing a period of urban renewal. Various residential and commercial developments are underway, particularly in the northern districts, while Bucharest’s historic centre is currently undergoing restoration.Geography

Main article: Geography of Romania

[edit] General information

The Dâmbovița River

Herăstrău Park

Cișmigiu

Titan Lake

Bucharest is situated on the banks of the Dâmbovița River, which flows into the Argeș River, a tributary of the Danube. Several lakes – the most important of which are Lake Herăstrău, Lake Floreasca, Lake Tei, and Lake Colentina – stretch across the city, along the Colentina River, a tributary of the Dâmbovița. In addition, in the centre of the capital there is a small artificial lake – Lake Cișmigiu – surrounded by the Cișmigiu Gardens. The Cișmigiu Gardens have a rich history, being frequented by famous poets and writers. Opened in 1847 and based on the plans of German architect Carl F.W. Meyer, the gardens are currently the main recreational facility in the city centre.

Besides Cișmigiu, Bucharest contains several other large parks and gardens, including Herăstrău Park and the Botanical Garden. Herăstrău is a large public park located in the north of the city, around Lake Herăstrău, and the site of the Village Museum, while the Bucharest’s botanical garden is the largest in Romania and contains over 10,000 species of plants, many of them exotic; it was once a pleasure park for the royal family.[12]

Bucharest is situated in the south eastern corner of the Romanian Plain, in an area once covered by the Vlăsiei forest, which, after it was cleared, gave way to a fertile flatland. As with many cities, Bucharest is traditionally considered to have seven hills, similar to the seven hills of Rome. Bucharest’s seven hills are: Mihai Vodă, Dealul Mitropoliei, Radu Vodă, Cotroceni, Spirei, Văcărești and Sf. Gheorghe Nou.

The city has a total area of 226 square kilometres (87 sq mi). The altitude varies from 55.8 metres (183.1 ft) at the Dâmbovița bridge in Cățelu, south-eastern Bucharest and 91.5 m (300.2 ft) at the Militari church. The city has a relatively round shape, with the centre situated approximately in the cross-way of the main north-south/east-west axes at the University Square. The milestone for Romanian’s Kilometre Zero is placed just south of University Square in front of the New St. George Church (Sfântul Gheorghe Nou) at St. George Square (Piaţa Sfântul Gheorghe). Bucharest’s radius, from University Square to the city limits in all directions, varies from about 10 to 12 km (6.25–7.5 mi).

Until recently, the regions surrounding Bucharest were largely rural, but after 1989, new suburbs started to be built around Bucharest, in the surrounding Ilfov county. Further urban consolidation is expected to take place from 2006, when the Bucharest metropolitan area was formed, which will incorporate various communes and the cities of Ilfov and surrounding counties.

[edit] Climate

Bucharest has a humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification Dfa). Due to its position on the Romanian Plain, the city’s winters can get windy, even though some of the winds are mitigated due to urbanisation. Winter temperatures often dip below 0 °C (32 °F), sometimes even dropping to −20 °C (−4 °F). In summer, the average temperature is approximately 23 °C (73 °F) (the average for July and August), despite the fact that temperatures frequently reach 35 °C (95 °F) to 40 °C (104 °F) in mid-summer in the city centre. Although average precipitation and humidity during summer are low, there are occasional heavy storms. During spring and autumn, average daytime temperatures vary between 17 °C (63 °F) to 22 °C (72 °F), and precipitation during this time tends to be higher than in summer, with more frequent yet milder periods of rain.

[hide]Climate data for Bucharest

Month Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Year

Record high °C (°F) 16

(61) 22

(72) 29

(84) 32

(90) 37

(99) 43

(109) 41

(106) 41

(106) 39

(102) 35

(95) 26

(79) 20

(68) 43

(109)

Average high °C (°F) 1.5

(34.7) 4.1

(39.4) 10.5

(50.9) 18

(64) 23.3

(73.9) 26.8

(80.2) 28.8

(83.8) 28.5

(83.3) 24.6

(76.3) 18

(64) 10

(50) 3.8

(38.8) 16.5

(61.7)

Average low °C (°F) -5.5

(22.1) -3.3

(26.1) 0.3

(32.5) 5.6

(42.1) 10.5

(50.9) 14

(57) 15.6

(60.1) 15

(59) 11.1

(52) 5.7

(42.3) 1.6

(34.9) -2.6

(27.3) 5.7

(42.3)

Record low °C (°F) -32

(-26) -26

(-15) -19

(-2) -4

(25) 0

(32) 5

(41) 8

(46) 7

(45) 0

(32) -6

(21) -14

(7) -23

(-9) -32

(-26)

Precipitation mm (inches) 40

(1.57) 36

(1.42) 38

(1.5) 46

(1.81) 70

(2.76) 77

(3.03) 64

(2.52) 58

(2.28) 42

(1.65) 32

(1.26) 49

(1.93) 43

(1.69) 595

(23.43)

% Humidity 87 84 73 63 63 62 58 59 63 73 85 89 72

Avg. precipitation days 6 6 6 7 6 6 7 6 5 5 6 6 72

Avg. snowy days 6 3 4 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 4 19

Sunshine hours 61 85 104 120 148 203 246 360 240 89 60 62 1,778

Source: World Meteorological Organisation [13]

[edit] Law and government

[edit] Administration

See also: Bucharest metropolitan area

Bucharest City Hall

Sorin Oprescu, the incumbent mayor since 2008

Bucharest has a unique status in Romanian administration, since it is the only municipality that is not part of a county. Its population, however, is larger than that of any Romanian county, and hence the power of the Bucharest General City Hall (Primăria Generală), which is the city’s local government body, is about the same as, if not greater than, that of Romanian county councils.

The city government is headed by a General Mayor (Primar General), currently (as of 2010) Sorin Oprescu. Decisions are approved and discussed by the General Council (Consiliu General) made up of 55 elected councilors. Furthermore, the city is divided into six administrative sectors (sectoare), each of which has their own 27-seat sectoral council, town hall and mayor. The powers of local government over a certain area are therefore shared by the Bucharest City Hall and the local sectoral councils with little or no overlapping of authority. The general rule is that the main City Hall is responsible for citywide utilities such as the water system, the transport system and the main boulevards, while sector halls manage the contact between individuals and the local government, secondary streets, parks, schools and cleaning services.

The 6 administrative sectors of Bucharest

The six sectors are numbered from one to six and are disposed radially so that each one has under its administration an area of the city centre. They are numbered clockwise and are further divided into neighborhoods (cartiere), which are not an official administrative division:

Sector 1 (population 227,717): Dorobanți, Băneasa, Aviației, Pipera, Aviatorilor, Primăverii, Romană, Victoriei, Herăstrău Park, Bucureștii Noi, Dămăroaia, Strǎulești, Grivița, 1 Mai, Băneasa Forest, Pajura, Domenii and a small part of Giulești which includes Giulești Stadium

Sector 2 (population 357,338): Pantelimon, Colentina, Iancului, Tei, Floreasca, Moşilor, Obor, Vatra Luminoasă, Fundeni, Plumbuita, Ștefan cel Mare, Baicului

Sector 3 (population 399,231): Vitan, Dudești, Titan, Centrul Civic, Dristor, Lipscani, Muncii, Unirii

Sector 4 (population 300,331): Berceni, Olteniței, Giurgiului, Progresul, Văcărești, Timpuri Noi, Tineretului

Sector 5 (population 288,690): Rahova, Ferentari, Giurgiului, Cotroceni, 13 Septembrie, Dealul Spirii

Sector 6 (population 371,060): Giulești, Crângași, Drumul Taberei, Militari, Grozǎvești (also known as Regie), Ghencea

Like all other local councils in Romania, the Bucharest sectoral councils, the city’s General Council and the mayors are elected every four years by the population. Additionally, Bucharest has a prefect, who is appointed by Romania’s central government. The prefect is not allowed to be a member of a political party. The prefect’s role is to represent the national government at local level, acting as a liaison and facilitating the implementation of National Development Plans and governing programs at local level. The current prefect of Bucharest (as of 2010) is Mihai Cristian Atanasoaiei.

The Municipality of Bucharest, along with the surrounding Ilfov county, forms the Bucharest development region, which is equivalent to NUTS-II regions in the European Union and is used by the European Union and the Romanian Government for statistical analysis and regional development. The Bucharest development region is not, however, an administrative entity.

[edit] Justice system

The Palace of Justice viewed across the Dâmbovița river

Bucharest’s judicial system is similar to that of the Romanian counties. Each of the six sectors has its own local first instance court (judecătorie), while appeals from these courts’ verdicts, and more serious cases, are directed to the Bucharest Tribunal, the city’s municipal court. The Bucharest Court of Appeal judges appeals against decisions taken by tribunals in Bucharest and in five surrounding counties (Teleorman, Ialomiţa, Giurgiu, Călăraşi and Ilfov). Bucharest is also home to Romania’s supreme court, the High Court of Cassation and Justice, as well as to the Constitutional Court of Romania.

Bucharest has its own municipal police force, the Bucharest Police (Poliția București), which is responsible for policing of crime within the whole city, and operates a number of special divisions. The Bucharest Police are headquartered on Ştefan cel Mare Blvd in the city centre, and has a number of precincts throughout the city. From 2004 onwards, each sector City Hall also has under its administration a Community Police force (Poliția Comunitară), dealing with local community issues. Bucharest also houses the General Inspectorates of the Gendarmerie and the National Police.

[edit] Crime

Main article: Crime in Bucharest

Bucharest’s crime rate is rather low in comparison to other European capital cities, with the number of total offenses declining by 51% between 2000 and 2004.[14] The violent crime rate in Bucharest remains very low, with 11 murders and 983 other violent offenses taking place in 2007.[15] Although there have been a number of recent police crackdowns on organized crime gangs, such as the Cămătaru clan, organized crime generally has little impact on public life. Petty crime, however, is more common, particularly in the form of pickpocketing, which occurs mainly on the city’s public transport network. Confidence tricks were sometimes common in the 1990s, especially in regards to tourists, but the frequency of these tricks has declined in recent years. Levels of crime are higher in the southern districts of the city, particularly in Ferentari, a socially-disadvantaged area.

Although the presence of street children was a problem in Bucharest in the 1990s, their numbers have declined significantly in recent years, currently lying at or below the average of major European capital cities.[16] A documentary Children Underground, depicted life of Romania street kids in 2001. The same is true for beggars and homeless people, many of them from the Roma minority. However, there are still an estimated 1,000 street children in the city,[16] many of whom engage in petty crime and begging. There has been speculation that the street children are recruited by professional underground networks for criminal purposes. From 2000 onwards, Bucharest has seen an increase in illegal road races which occur mainly at night in the city’s outskirts or on industrial sites.

[edit] Stray dogs

When Centrul Civic was built, approximately 40,000 families and 3,000 pet dogs were dispossessed of their homes. Most of these dogs became strays, and rapid breeding led to a population of over 250,000 stray dogs by 2001. Mayor Traian Băsescu had initially planned to euthanize as many stray dogs as possible, but international outcry — led by actress Brigitte Bardot — resulted in the substitution of a spay-and-release program instead.[17]

[edit] Quality of Life

As stated by the Mercer international surveys for quality of life in cities around the world, Bucharest occupied the 94th place in 2001[18] and slipped lower, to the 108th place in 2009. Vienna occupied #1 worldwide in 2009 .[19]

[edit] Demographics

Main article: Demographics of Romania

Historical population of Bucharest Year Population

1789 30,030

1831 increase 60,587

1859 increase 122,000

1900 increase 282,071[20]

1912 census increase 341,321[21]

1918 increase 383,000

December 29, 1930 census increase 633,355[22]

January 25, 1948 census increase 1,025,180[22]

February 21, 1956 census increase 1,177,661[22]

March 15, 1966 census increase 1,366,684[22]

January 5, 1977 census increase 1,807,239[22]

July 1, 1990 estimate increase 2,127,194

January 7, 1992 census decrease 2,067,545[22]

March 18, 2002 census decrease 1,926,334[22]

July 1, 2007 estimate increase 1,931,838[23]

January 1, 2009 estimate increase 1,944,367[2]

The city’s population, according to the 2002 census, is 1,926,334 inhabitants,[22] or 8.9% of the total population of Romania. Additionally, due to the recent process of gentrification there are now more than 200,000 people commuting to the city every day, mainly from the surrounding Ilfov county[citation needed].

Bucharest’s population experienced two phases of rapid growth, the first in the late 19th century, when the city grew in importance and size, and the second during the Communist period, when a massive urbanization campaign was launched and many people migrated from rural areas to the capital. At this time, due to Ceauşescu’s ban on abortion and contraception, natural increase was also significant.

Approximately 96.9% of the population of Bucharest are Romanians. The second largest ethnic group being are Roma (Gypsies), which make up 1.4% of the population. Other significant ethnic groups are Hungarians (0.3%), Jews (0.1%), Turks (0,1%), Chinese (0,1) and Germans (0,1%). A relatively small number of Bucharesters are of Greek, North American, French, Armenian, Lippovan and Italian descent. The Greeks and the Armenians used to play significant roles in the life of the city at the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century. One of the predominantly Greek neighborhoods was Vitan – where a Jewish population also lived; the latter was more present in Văcărești and areas around Unirii Square.

In terms of religion, 96.1% of the population are Romanian Orthodox, 1.2% are Roman Catholic, 0.5% are Muslim and 0.4% are Romanian Greek Catholic. Despite this, only 18% of the population, of any religion, attend a place of worship once a week or more.[24] The life expectancy of residents of Bucharest in 2003–2005 was 74.14 years, around 2 years higher than the Romanian average. Female life expectancy was 77.41 years, in comparison to 70.57 years for males.[25]

Panoramic view of the city centre

[edit] Economy

Tower Center International

Main article: Economy of Bucharest

Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Romania Building

Bucharest is the centre of the Romanian economy and industry, accounting for around 14.6% of the country’s GDP and about one-quarter of its industrial production, while being inhabited by only 9% of the country’s population.[26] Almost one third of national taxes is paid by Bucharest’s citizens and companies. In 2007, at purchasing power parity, Bucharest had a per-capita GDP of €20,057, or 92.2% that of the European Union average and more than twice the Romanian average.[27] The city’s strong economic growth has revitalized infrastructure and led to the development of many shopping malls and modern residential towers and high-rise office buildings. In September 2005, Bucharest had an unemployment rate of 2.6%, significantly lower than the national unemployment rate of 5.7%.[28]

Bucharest’s economy is mainly centred on industry and services, with services particularly growing in importance in the last ten years. The headquarters of 186,000 firms, including nearly all large Romanian companies are located in Bucharest.[29] An important source of growth since 2000 has been the city’s rapidly expanding property and construction sector. Bucharest is also Romania’s largest centre for information technology and communications and is home to several software companies operating offshore delivery centres. Romania’s largest stock exchange, the Bucharest Stock Exchange, which was merged in December 2005 with the Bucharest-based electronic stock exchange Rasdaq plays a major role in the city’s economy.

There are a number of major international supermarket chains such as Carrefour, Cora and METRO. At the moment, the city is undergoing a retail boom, with a large number of supermarkets, and hypermarkets, constructed every year. For more information, see supermarkets in Romania. A few of the largest and most modern shopping centres in Bucharest are AFI Palace Cotroceni, Sun Plaza, Băneasa Shopping City, Bucharest Mall, Plaza Romania, City Mall, Jolie Ville Galleria, Liberty Center and Unirea Shopping Center. There are also a large number of traditional retail arcades and markets; the one at Obor covers about a dozen city blocks and numerous large stores that are not officially part of the market effectively add up to a market district almost twice that size.

[edit] Transport

Bucharest public bus

Bucharest Metro, Berceni station

A geographically accurate Bucharest Metro map

Main article: Transport in Bucharest

[edit] Public transport

Bucharest’s extensive public transport system is the largest in Romania and one of the largest in Europe. It is made up of the Bucharest Metro, as well as a surface transport system run by RATB (Regia Autonomă de Transport București), which consists of buses, trams, trolleybuses, and light rail. In addition, there is a private minibus system. As of 2007, there is a limit of 10,000 taxicab licenses,[30] down from 25,000 in the 1990s, and the even higher demand is supplied by taxis registered in Ilfov county.

[edit] Railways

Bucharest is the hub of Romania’s national railway network, run by Căile Ferate Române. The main railway station is Gara de Nord, or North Station, which provides connections to all major cities in Romania as well as international destinations :

Belgrade (Serbia)

Budapest (Hungary)

Sofia, Varna (Bulgaria)

Chișinău (Republic of Moldova)

Kyiv, Chernivtsi, Lviv (Ukraine)

Thessaloniki (Greece)

Vienna (Austria)

Istanbul (Turkey)

Moscow (Russia)

The city also has five other railway stations run by CFR, most important are Basarab (in proximity of North Station), Obor, Baneasa, Progresu, which are in the process of being integrated in a commuter railway serving Bucharest and the surrounding Ilfov county. 7 main lines radiate out of Bucharest.

[edit] Air

Main article: Transport in Bucharest

Henri Coandă International Airport

Bucharest has two international airports:

Henri Coandă International Airport, located 16.5 km (10.3 mi) north of the Bucharest city center, in the town of Otopeni, Ilfov. Currently the airport has one terminal divided into two inter-connected buildings (Departures Hall and Arrivals Hall). The International Departures Hall consists of 36 check-in desks, one finger with 24 gates (14 equipped with jetways), while the Domestic Hall has an extra four gates. Today’s Arrivals Hall is actually the old Otopeni terminal, while the new Departures Hall, including the finger and the airbridges was built and inaugurated in 1997. An expansion of the finger was opened in March 2011, other expansions of Departure Hall and Arrivals Hall are underway and a new terminal on the east side is in project phase. The airport received 4,917,952 passengers in 2010.

Aurel Vlaicu International Airport is situated only 8 km (5.0 mi) north of the Bucharest city center and is accessible by RATB buses 131, 335, 301, tramway 5 and Airport Express 783 and taxi. An extension of Line M2 of the Bucharest Metro to Aurel Vlaicu International, which will link it to the Main Train Station and the larger Henri Coandă International Airport, was approved in June 2006 and is currently in its planning stage. In 2010, the airport received 2,118,150 passengers.

[edit] Roads

Traffic congestion in Băneasa

Bucharest is also a major intersection of Romania’s national road network. A few of the busiest national roads and motorways, link the city to all of Romania’s major cities as well as to neighbouring countries such as Hungary, Bulgaria and Ukraine. The A1 to Pitesti and the A2 Sun Motorway to the Dobrogea region and Constanta both start from Bucharest. The future A3 and A5 motorways will radiate from Voluntari, a town in the city’s northern outskirts.

[edit] Infrastructure

The city’s municipal road network is centred around a series of high-capacity boulevards, which generally radiate out from the city centre to the outskirts. The main axes, which run north-south, east-west and northwest-southeast, as well as one internal and one external ring road, support the bulk of the traffic. The city’s roads are usually very crowded during rush hours, due to an increase in car ownership in recent years. Every day, there are more than one million vehicles travelling within the city.[31] This results in occasional wear and potholes appearing on busy roads, particularly secondary roads, this being identified as one of Bucharest’s main infrastructural problems. In recent years, there has been a comprehensive effort on behalf of the City Hall to boost road infrastructure and according to the general development plan, 2,000 roads have been repaired by 2008.[32]

[edit] Water

Although it is situated on the banks of a river, Bucharest has never functioned as a port city, with other Romanian cities such as Constanța and Galați acting as the country’s main ports. However, the Danube-Bucharest Canal, which is 73 km (45 mi) long, is currently in construction and is around 60% completed.[citation needed] When finished, the canal will link Bucharest to the Danube River and, via the Danube-Black Sea Canal, to the Black Sea. This corridor is expected to be a significant component of the city’s transport infrastructure and increase sea traffic by a large margin.

[edit] Culture

Main article: Culture of Romania

Central University Library

Bucharest has a diverse and growing cultural scene, with cultural life exhibited in a number of various fields, including the visual arts, performing arts and nightlife. Unlike other parts of Romania, such as the Black Sea coast or Transylvania, Bucharest’s cultural scene is much more eclectic, without a defined style, and instead incorporates various elements of Romanian and international culture. Bucharest has an eclectic mixture of elements from traditionally Romanian buildings to buildings that are influenced by French architects. It is because of this French influence that Bucharest was once called “the Paris of the East” or “Little Paris.”

[edit] Landmarks

Palace of the Parliament (Chamber of Deputies)

Arcul de Triumf

The Romanian Athenaeum

Aerial view of Calea Victoriei, one of the city’s main roads

The National Bank of Romania

Bucharest has a large number of landmark buildings and monuments. Perhaps the most prominent of these is the Palace of the Parliament, built in the 1980s during the reign of Communist dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu. Currently the largest building in Europe and the second-largest in the world, the Palace houses the Romanian Parliament (the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate), as well as the National Museum of Contemporary Art. The building also boasts one of the largest convention centres in the world.

Another well-known landmark in Bucharest is Arcul de Triumf (The Triumphal Arch), it was built in its current form in 1935 and modeled after the Arc de Triomphe in Paris. A newer landmark of the city is the Memorial of Rebirth, a stylized marble pillar unveiled in 2005 to commemorate the victims of the Romanian Revolution of 1989, which overthrew Communism. The abstract monument sparked a great deal of controversy when it was unveiled, being dubbed with names such as “the olive in the toothpick”, (“măslina-n scobitoare”), as many argued that it does not fit in its surroundings and believed that its choice was based on political reasons.[33]

The Romanian Athenaeum building is considered to be a symbol of Romanian culture and since 2007 is on the list of the Label of European Heritage sights.[34]

Other cultural venues include the National Museum of Art of Romania, Museum of Natural History “Grigore Antipa”, Museum of the Romanian Peasant (Muzeul Ţăranului Român), National History Museum, and the Military Museum.

[edit] Visual arts

In terms of visual arts, the city contains a number of museums featuring both classical and contemporary Romanian art, as well as selected international works. The National Museum of Art of Romania is perhaps the best-known of Bucharest museums. It is located in the former royal palace and features extensive collections of medieval and modern Romanian art, including works by renowned sculptor Constantin Brâncuși, as well as a prominent international collection assembled by the former Romanian royal family.

Other, smaller museums, contain more specialised collections of works. The Zambaccian Museum, which is situated in the former home of Armenian-Romanian art collector Krikor H. Zambaccian contains works by many well-known Romanian artists as well as international artists such as Paul Cézanne, Eugène Delacroix, Henri Matisse, Camille Pissarro and Pablo Picasso.

The Gheorghe Tattarescu Museum contains portraits of Romanian revolutionaries in exile such as Gheorghe Magheru, Ștefan Golescu, Nicolae Bălcescu and allegorical compositions with revolutionary (Romania’s rebirth, 1849) and patriotic (The Principalities’ Unification, 1857) themes. The Theodor Pallady Museum is situated in one of the oldest surviving merchant houses in Bucharest and includes many works by Romanian painter Theodor Pallady as well as a number of European and Oriental furniture pieces. The Museum of Art Collections contains the collections of a number of well-known Romanian art aficionados, including Krikor Zambaccian and Theodor Pallady.

Despite the extensive classical art galleries and museums in the city, there is also a contemporary arts scene that has become increasingly prominent in recent times. The National Museum of Contemporary Art (MNAC), situated in a wing of the Palace of the Parliament, was opened in 2004 and contains a widespread collection of Romanian and international contemporary art, in a number of expressive forms. The MNAC also manages the Kalinderu MediaLab, which caters specifically to multimedia and experimental art. There is also a range of smaller, private art galleries throughout the city centre.

The palace of the National Bank of Romania houses the national numismatic collection. Exhibits include banknotes, coins, documents, photographs, maps, silver and gold bullion bars, bullion coins, dies and moulds. The building itself was constructed between 1884 and 1890. The thesaurus room contains notable marble decorations.

[edit] Performing arts

Odeon Theatre

The Romanian National Opera

Performing arts are one of the strongest cultural elements of Bucharest, and the city has a number of world-renowned facilities and institutions. The most famous symphony orchestra is National Radio Orchestra of Romania. One of the most prominent buildings is the neoclassical Romanian Athenaeum, which was founded in 1852, and hosts classical music concerts, the George Enescu Festival, and is home to the “George Enescu” Philharmonic. Bucharest is also home to the Romanian National Opera, as well as the I.L. Caragiale National Theatre. Another well-known theatre in Bucharest is the State Jewish Theatre, which has gained increasing prominence in recent years due partly to the fact that it features plays starring world-renowned Romanian-Jewish actress Maia Morgenstern. There is also a large number of smaller theatres throughout the city that cater to specific genres, such as the Comedy Theatre, the Nottara Theatre, the Bulandra Theatre, the Odeon Theatre, and the Constantin Tănase Revue Theatre.

[edit] Music and nightlife

Bucharest is home to Romania’s largest recording labels, and is often the residence of Romanian musicians. The city’s music scene is eclectic. Many Romanian rock bands of the 1970s and 1980s, such as Iris and Holograf, continue to be popular, particularly with the middle-aged, while since the beginning of the 1990s the hip hop/rap scene has developed a unique sound and style indigenous to eastern Bucharest. Hip-hop bands and artists from Bucharest such as B.U.G. Mafia, Paraziţii, Verdikt, La familia, Sisu & Puia, Bitză and Zale enjoy national and international recognition.

Strada Franceză in Bucharest’s Historical Centre

The eclectic pop-rock band Taxi have been gaining international respect, as has Spitalul de Urgenţă’s raucous updating of traditional Romanian music. While many neighbourhood discos play manele, an Oriental- and Roma-influenced genre of music that is particularly popular in Bucharest’s working class districts, the city has a rich jazz and blues scene, and, to an even larger extent, house music/trance and heavy metal/punk scenes. Bucharest’s jazz profile has especially risen since 2002, with the presence of two thriving venues, Green Hours and Art Jazz, as well as an American presence alongside established Romanians. The city’s nightlife, particularly its club scene grew significantly in the 1990s, and continues to develop.

There is no central nightlife strip, with many entertainment venues dispersed throughout the city centre, with a cluster in the historical centre. Among the most visited venues are Lăptăria Enache and La Motoare, located on the rooftop of the National Theatre, as well as El Grande Comandante and Club A. Most clubs and bars are located around the centre of the city, from Unification Square to Roman Square. Also, a large concentration of rock clubs can be found in the Lipscani area, the old part of the city, in the vicinity of Piaţa Unirii. The Regie area, located near Polytechnic University campus, hosts a number of clubs and bars, mainly targeted toward the student population.

The city also hosts some of the best electronic music clubs in Europe such as Studio Martin and Kristal Glam Club.[citation needed] During the summer, Zoom Beach Club is an outdoor club on the shore of a lake and has two separate dance floors. The Office is one of the most exclusive clubs in Bucharest and has a long tradition in clubbing. One of the best cocktail clubs in Bucharest is Deja Vu situated on Bălcescu Boulevard near the Italian church. Some other notable venues are: Gaia, Fratelli, Glamour, Tipsy, Cotton Club, Pat, and Bamboo.

[edit] Traditional culture

Bucharest’s cultural life has, especially since the early 1990s, become colourful and worldly. Traditional Romanian culture, however, continues to have a major influence in arts such as theatre, film and music. Additionally, Bucharest has two internationally-renowned ethnographic museums, the Museum of the Romanian Peasant and the open-air Village Museum. The Village Museum, in Herăstrău Park, contains 272 authentic buildings and peasant farms from all over Romania. The Museum of the Romanian Peasant was declared the European Museum of the Year in 1996, and displays a rich collection of textiles (especially costumes), icons, ceramics, and other artifacts of Romanian peasant life.

The Museum of Romanian History is another important museum in Bucharest, containing a collection of artefacts detailing Romanian history and culture from the prehistoric times, Dacian era, medieval times and the modern era.

[edit] Cultural events and festivals

George Enescu Festival

The Palace of the Patriarchate

There are a number of cultural festivals in Bucharest throughout the year, in various domains, even though most festivals take place in the summer months of June, July and August. The National Opera organises the International Opera Festival every year in May and June, which includes ensembles and orchestras from all over the world. The Romanian Athaeneum Society hosts the George Enescu Festival at various locations throughout the city in September every two years (odd years). Additionally, the Museum of the Romanian Peasant and the Village Museum organise a number of events throughout the year showcasing Romanian folk arts and crafts.

In the first decade of the 21st century, due to the growing prominence of the Chinese community in Bucharest, several Chinese cultural events have taken place. The first officially-organised Chinese festival was the Chinese New Year’s Eve Festival of February 2005 which took place in Nichita Stănescu Park and was organised by the Bucharest City Hall.[35] In 2005, Bucharest was the first city in Southeastern Europe to host the international CowParade, which resulted in dozens of decorated cow sculptures being placed at various points across the city.

Since 2005 Bucharest has its own contemporary art biennale, the Bucharest Biennale. The next edition will be in 2010.

[edit] Religious life

Bucharest is the seat of the Patriarch of the Romanian Orthodox Church, one of the Eastern Orthodox churches in communion with the Patriarch of Constantinople, and also of its subdivisons, the Metropolis of Muntenia and Dobrudja and the Archbishopric of Bucharest. Orthodox believers say that Saint Demetrios is the patron saint of the city.

Bucharest is also a center for various other religions and cults in Romania, including the main Romanian-ethnic Catholic organization, Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Bucharest.

[edit] Architecture

Old CEC Palace in front of Bucharest Financial Plaza

Bucharest’s architecture is highly eclectic due to the many influences on the city throughout its history. The city centre is a mixture of medieval, neoclassical and art nouveau buildings, as well as ‘neo-Romanian’ buildings dating from the beginning of the 20th century and a remarkable collection of modern buildings from the 20s and 30s. The mostly-utilitarian Communist-era architecture dominates most southern boroughs. Recently built contemporary structures such as skyscrapers and office buildings complete the landscape.

[edit] Historical architecture

The Creţulescu Palace

The courtyard of Manuc’s Inn

Of the city’s medieval architecture, most of what survived into modern times was destroyed by Communist systematization, numerous fires and military incursions. Still, some medieval and renaissance edifices remain, the most notable are in the Lipscani area. This precinct contains notable buildings such as Manuc’s Inn and the ruins of the Curtea Veche (the Old Court), during the late Middle Ages this area was the heart of commerce in Bucharest. From the 1970s onwards, the area went through urban decline, and many historical buildings fell into disrepair. In 2005, the Lipscani area was entirely pedestrianised and is currently slowly undergoing restoration.

The city centre has also retained architecture from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, particularly the interwar period, which is often seen as the “golden age” of Bucharest architecture. During this time, the city grew significantly in size and wealth therefore seeking to emulate other large European capitals such as Paris. Much of the architecture of the time belongs to a remarkably strong Modern (rationalist) Architecture current, led by Horia Creanga and Marcel Iancu, which managed to literally change the face of the city.

Two notable buildings from this time are the Crețulescu Palace, currently housing cultural institutions including UNESCO’s European Centre for Higher Education, and the Cotroceni Palace, the current residence of the Romanian President. Many large-scale constructions such as Gara de Nord, the busiest railway station in the city, National Bank of Romania’s headquarters and the Telephone Palace date from these times. In the first decade of the 21st century, a wide variety of historic buildings in the city centre underwent restoration. In some residential areas of the city, particularly the high-income northern suburbs, there are many turn-of-the-century villas, most of which were restored in the late 1990s.

[edit] Communist architecture

Parliament of Romania balcony

A major part of Bucharest’s architecture is made up of buildings constructed during the Communist era replacing the historical architecture with high density apartment blocks – significant portions of the historic center of Bucharest were demolished in order to construct one of the largest buildings in the world: Casa Poporului – Palace of the Parliament. In Nicolae Ceaușescu’s project of systematization many new buildings were built in previously-historical areas, which were razed and then built upon from scratch.

One of the best examples of this type of architecture is Centrul Civic, a development that replaced a major part of Bucharest’s historic city centre with giant utilitarian buildings, mainly with marble or travertine façades, inspired by North Korean architecture. Communist-era architecture can also be found in Bucharest’s residential districts, mainly in blocuri, which are high-density apartment blocks that house the majority of the city’s population.

[edit] Contemporary architecture

The Casa Radio project, currently under construction

Howard Johnson Hotel

Since the fall of Communism in 1989, several Communist-era buildings have been refurbished, modernised and used for other purposes. Perhaps the best example of this is the conversion of several obsolete retail complexes into shopping malls and commercial centres. These giant circular halls, which were unofficially called hunger circuses due to the food shortages experienced in the 1980s, were constructed during the Ceaușescu era to act as produce markets and refectories, although most were left unfinished at the time of the Revolution.

Modern shopping malls like Unirea Shopping Center, Bucharest Mall, Plaza Romania and City Mall emerged on pre-existent structures of former hunger circuses. Another example is the modernisation and conversion of a large utilitarian construction in Centrul Civic into a Marriott Hotel. This process was accelerated after 2000, when the city underwent a property boom, and many Communist-era buildings in the city centre became prime real estate due to their location. In recent years, many Communist-era apartment blocks have also been refurbished to improve urban appearance.

The newest contribution to Bucharest’s architecture took place after the fall of Communism, particularly after 2000, when the city went through a period of urban renewal – and architectural revitalization – on the back of Romania’s rapid economic growth. Buildings from this time are mostly made of glass and steel, and often have more than ten storeys. Examples include shopping malls (particularly the Bucharest Mall, a conversion and extension of an abandoned building), office buildings, bank headquarters, the Bucharest World Trade Center and the Chamber of Commerce, which lies on the banks of the Dâmbovița.

As of 2005, there is a significant number of office buildings in construction, particularly in the northern and eastern parts of the city. Additionally, there has been a trend in recent years to add modern wings and façades to historic buildings, the most prominent example of which is the Bucharest Architects’ Association Building, which is a modern glass-and-steel construction built inside a historic stone façade.

Aside from buildings used for business and institutions, various new residential developments are currently underway, many of which consist of high-rise buildings with a glass exterior, surrounded by American-style residential communities. These developments are increasingly prominent in the northern suburbs of the city, which are less densely-populated and are home to a significant number of middle- and upper-class Bucharesters due to the process of gentrification.

[edit] Media

View over Kiseleff Road, with Casa Presei Libere visible in the distance

Bucharest is the most important centre of the Romanian media, since it is the headquarters of all the national television networks as well as national newspapers and radio stations. The largest daily newspapers in Bucharest include Evenimentul Zilei, Jurnalul Național, Cotidianul, România Liberă, Adevărul, Gardianul and Gândul. During the rush hours, tabloid newspapers Click!, Libertatea and Ziarul are very popular for commuters.

A significant number of newspapers and media publications are based in Casa Presei Libere (The House of the Free Press), a landmark of northern Bucharest, originally named Casa Scânteii after the Communist-era official newspaper Scînteia. Casa Presei Libere is not the only Bucharest landmark that grew out of the media and communications industry. Palatul Telefoanelor (“The Telephone Palace”) was the first major modernist building on Calea Victoriei in the city’s centre, and the massive, unfinished communist-era Casa Radio looms over a park a block away from the Opera.

English-language newspapers first became available in the early 1930s and reappeared in 1990s, becoming increasingly prominent since then. There are two daily English-language newspapers, Bucharest Daily News and Nine O’ Clock, as well as numerous other magazines. A number of publications in other languages are also available, such as the Hungarian-language daily Új Magyar Szó.

Observator Cultural covers the city’s arts, and the free weekly magazines Șapte Seri (“Seven Evenings”) and B24FUN, list entertainment events of all sorts. The city is also home to the intellectual journal Dilema, the satire magazine Academia Cațavencu, as well as a wide array of commercial magazines.

Bucharest was the host city of the fourth edition of the Junior Eurovision Song Contest 2006.

[edit] Education

Romanian-American University

Academy of Economic Studies main building

There are 16 public universities in Bucharest, the largest of which are the University of Bucharest, the Bucharest Academy of Economic Studies, the Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, and the Politehnica University of Bucharest. These are supplemented by 19 private universities, such as the Romanian-American University and the Spiru Haret University. Overall, there are 159 faculties in 34 universities. Private universities have a mixed reputation due to irregularities in the educational process[36] as well as perceived corruption.[37] As in the rest of Romania, universities in Bucharest are lower in world rankings compared to their American and Western European counterparts.[38] However, in recent years the city has seen an increasing influx of foreign students who come to study there, primarily from Asia.[39]

The first modern educational institution was the Princely Academy of Bucharest, founded in 1694 and divided in 1864 to form the present-day University of Bucharest and the Saint Sava National College, both of which are amongst the most prestigious of their kind in Romania.

There are around 450 public primary and secondary schools in the city, all of which are administered by the Bucharest Municipal Schooling Inspectorate. Each sector also has its own Schooling Inspectorate, subordinated to the Municipal one.

[edit] Sports

The new Lia Manoliu National Stadium will host the 2012 Europa League final

Bucharest Ring, a street circuit in the city centre of Bucharest

Football is the most widely-followed sport in Bucharest, with the city having numerous club teams, some of them being known throughout Europe. Four Bucharest-based football teams participate in Liga 1, the first division in Romania: Steaua, Dinamo, Rapid and Sportul Studențesc.

The Lia Manoliu Stadium was the national stadium and the largest stadium in Romania. It has now been demolished to make way for a new stadium, which will host the 2012 Europa League Final.

There are also a number of sport clubs for ice hockey, rugby union, basketball, handball, water polo and volleyball. The majority of Romanian track and field athletes, boxers, and a great number of gymnasts are affiliated with clubs in Bucharest. The Athletics and many Gymnastics National Championships are held in Bucharest.

The biggest hall in Bucharest is Sala Polivalentă and has a seating capacity of 6,000. It is frequently used for concerts, indoor sports such as volleyball, exhibitions and shows.

Starting in 2007 Bucharest has hosted annual races along a temporary urban track surrounding the Palace of the Parliament, called Bucharest Ring. The competition is called the Bucharest City Challenge, and has hosted FIA GT, FIA GT3, British F3, and Logan Cup races in 2007 and 2008. The 2009 and 2010 edition have not been held in Bucharest due to a lawsuit. Bucharest GP, owned by the controversial businessman Nicolae Șerbu, won the lawsuit that it initiated and will host city races around the Parliament starting 2011 with the Auto GP[40]

Every autumn, Bucharest hosts BCR Open Romania international tennis tournament, which is included in the ATP Tour. The outdoors tournament is hosted by the tennis complex BNR Arenas. The ice hockey games are held at the Mihai Flamaropol Arena, which holds 8,000 spectators. The rugby games are held in different locations, but the most modern stadium is Arcul de Triumf Stadium, where also the Romanian national rugby team plays.

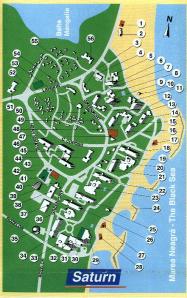

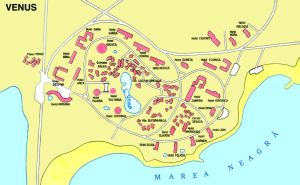

BUCURESTI MAP TOURIST GHID